One of GIFT‘s main work streams has been strengthening standards and norms on fiscal transparency. And one of the key gaps identified from the outset is the lack of transparency of the environmental impacts of fiscal policies.

Principle four of the GIFT High-level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation and Accountability states: ‘Governments should communicate the objectives they are pursuing and the outputs they are producing with the resources entrusted to them, and endeavour to assess and disclose the anticipated and actual social, economic and environmental outcomes’ (italics added).

Until very recently, however, there has been little guidance on disclosure of the environmental impacts of fiscal policies, aside from requirements for publication of environmental impact assessments at the individual project level (see discussion in the GIFT Expanded Version of HLP4).

This is despite the challenge issued in 1987 by the Brundtland Commission: ‘the major central economic agencies of governments should now be made directly responsible for ensuring that their policies and budgets support ecologically sustainable development.’ This remains an appropriate if still distant level of aspiration and is far more urgent than it was in 1987 given the twin existential threats of climate change and loss of biodiversity.

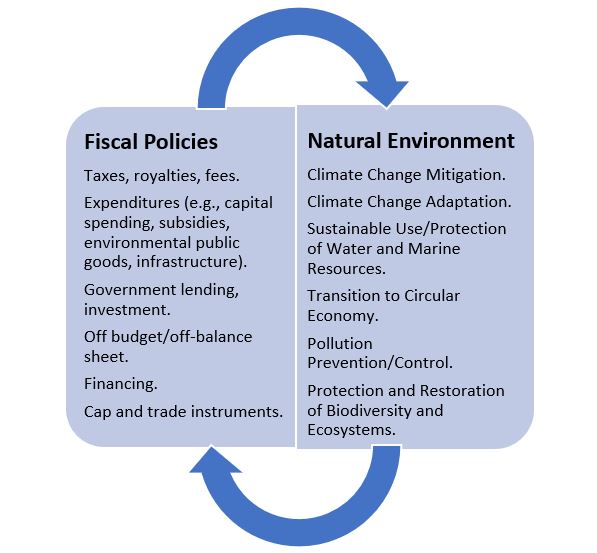

There are increasingly important impacts of fiscal policies on the environment, both environmentally harmful and beneficial impacts, and environmental degradation has growing fiscal impacts and poses escalating fiscal risks – as illustrated below.

Figure 1: Fiscal policies and the environment: two-way interactions (from Petrie, 2021).

The government’s annual budget cycle is widely recognized as its most important policy statement and most powerful policy integration and mainstreaming instrument. While regulation is critically important for environmental stewardship there is no annual regulatory policy cycle or process that could integrate and mainstream environmental goals into government strategy, cross-sector prioritization, and policy implementation. And in countries with multi-year national planning frameworks these must be implemented largely through annual budget allocations for the public investment projects that are generally the focus of National Development Plans.

The greening of fiscal policy is therefore the key tool to mainstream environmental objectives, targets, and instruments into government strategy and policy and to make governments more accountable for environmental stewardship. Over the last few decades fiscal strategies have increasingly incorporated social policy goals and indicators alongside economic and fiscal goals but also need to integrate key environmental indicators and risks.

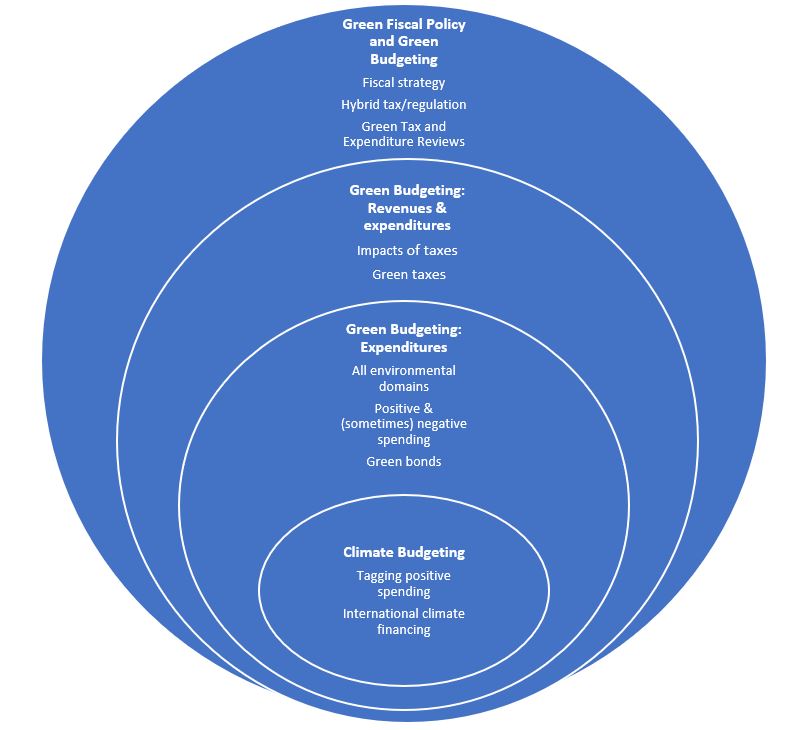

Work at the interfaces between fiscal policies and the environment is at an early stage. A variety of approaches have emerged over the last decade, described variously as climate budgeting, green budgeting, and green fiscal policy – as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 2: Climate Budgeting, Green Budgeting, and Green Fiscal Policy (from Petrie, 2021).

With only one exception (France), climate and green budgeting to date have been confined to reporting activities intended to promote positive environmental outcomes. Yet governments around the world continue to spend vast sums on direct subsidies and tax concessions for brown activities while paying lip service to their green credentials.

Climate and green budgeting to date has also focused on the expenditure side of the budget. Yet green taxes have a crucial role to play in reversing environmental degradation. As Nobel Laureate William Nordhaus has observed, green taxes ‘…are the holy trinity of environmental policy: they pay for valuable public services, they meet our environmental objectives efficiently, and they are non-distortionary. Few policies can be endorsed with such enthusiasm.’

What is required therefore is the progressive incorporation of environmental objectives, targets, analysis, and filters across the budget cycle, in tax policy, and in the public investment management cycle. Key entry points for the greening of fiscal policy are:

- the new policies in budgets (and COVID recovery packages), which need to be systematically tested for consistency with international environmental commitments and national targets. There is often no need to trade off the environment against economic growth, there are increasing win-win opportunities that are good for the economy and jobs as well as good for the planet e.g., renewable electricity, nature-based solutions for ecosystem resilience, increasing the energy efficiency of existing buildings through retrofitting, clean R&D spending, public works programs to provide income support to the poor (e.g., irrigation, tree planting, invasive species removal).

- the on-going tax and expenditure policies that are known to be the most environmentally damaging, such as subsidies for fossil fuels.

- taxing environmental externalities (green taxes) and earmarking the proceeds (including from cap-and- trade schemes) to public expenditure programs e.g., to fund mitigation, adaptation, transitional assistance to those most adversely affected by green taxes.

- integrating climate and the environment across the public investment management cycle to stop further investments in dirty technologies that will either lock in emissions and pollution for decades or create stranded assets that will need to be prematurely scrapped.

- introducing climate (green) budget tagging for countries seeking to attract international climate (green) finance. International climate finance is the main means of reconciling equity – developing countries have contributed little to global warming – with effectiveness and efficiency – some of the biggest emitters are now developing countries, and a large share of the required mitigation is required in developing countries if global emissions targets are to be met.

As with fiscal policy generally it will be critically important to ensure a high degree of transparency and accountability through governments progressively presenting a range of supplementary green budget documents and periodic green fiscal reports to the legislature and the public. This should include direct public engagement with traditionally excluded or marginalised voices, and enabling civil society to monitor, call out ‘green washing’, and promote the public interest over the interests of elites. This could involve the development of new tools such as a Green Guide to the Budget produced by civil society.

Incorporating environmental considerations into budgeting and fiscal policy will be a long process, reflecting both the complexity and scope of the task and the low starting point. Development and early implementation of new governance approaches is underway. But much more work is required to fill in the gaps and flesh out the details. The aim should be to rapidly develop a set of widely accepted international standards and norms for green fiscal policy and to launch major investments in the data, analysis, and capacity to progressively implement them.